|

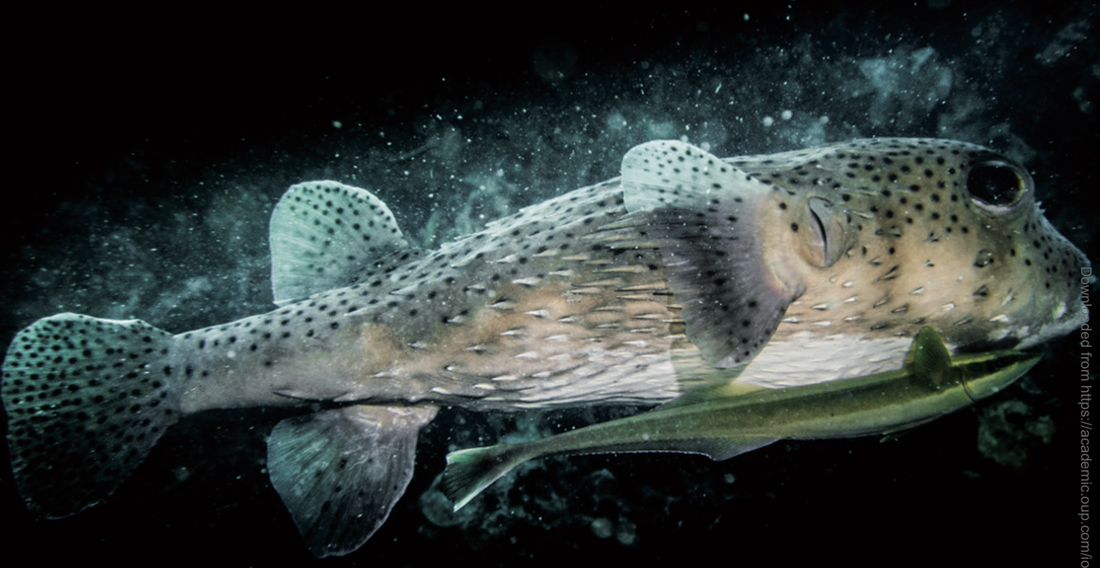

This post is well overdue, being slightly over a year after my last post. At that time we were in a lull between the first and second COVID waves, so we were allowed back in the office. However, as we all know now, that was short lived and LA suffered terrible case numbers in the fall and into the winter. While cases waned in the spring as vaccines became more available, we are now seeing numbers rise once again due to the delta variant. This past year has been incredibly difficult on so many levels. Difficult for the community. Difficult individually. Difficult for morale and optimism. Nevertheless, we continue to push on. The museum is back open to the public after a year with closed doors and empty exhibit halls. Due to the tremendous effort of so many staff members, our doors were opened in April. We started slow, with limited capacity and only a few days a week, but we got our feet back under us and are now open 6 days a week. It is such a great feeling to see visitors once again roaming the halls and to hear kids gasping with amazement when they see the dinosaurs towering over them. This last year the Department of Ichthyology has been silently chugging along. While I usually write a post here for each publication that comes out, I've let them pile up this time. Since the last post, though, I have been fortunate enough to be included on four publications. Two of these are on anti-tropicality in fishes, a topic near and dear to my heart. The age old question for this strange latitudinally disjunct distribution is wether species crossed the tropics from one hemisphere to the other, or if they were widespread and then split by the tropics. This is the debate of dispersal vs. vicariance, a topic that has played out many times in the literature over the decades. In the first of the anti-tropical publications we put out last year, I examine this question using ecological niche models with Dr. Corinne Myers from the University of New Mexico. This was a novel way of looking at this problem that gave us insight into the history of this pattern that we couldn't get with previous approaches. Ultimately we find that it's a mixture of both mechanisms, and it depends on the fish in question. This project was a long time coming (there are blog posts about it on this website dating back years ago), and I'm thrilled to finally see it out in print. Working on that paper also got me excited to write more about this pattern in general, and shortly after that publication came out I published a review paper on anti-tropicality in marine organisms in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. This summarizes all the work that has been done on this pattern in the last 20 years or so, and points to a few forward moving directions the field could go. It's open access, so go check it out! The last two publications were fun collaborations with current, and former, coworkers. The first was a publication led by NMHLA terrestrial mammal curator, Dr. Kayce Bell, is a call to action for depositing urban voucher specimens in natural history museums for current and future researchers to access and use. Without depositing these specimens we are only missing out on possible patterns and trends associated with our anthropogenic impacts on wildlife. That note came out in BioScience, so take a look if you're interested. The most recent publication that I was a part of was led by the talented Dr. Fernando Alda. This project was a fun collaboration of old LSU Chakrabarty lab members and used genomic approaches to look at the evolutionary relationships of neotropical cichlids. We then compared our data to another genomic dataset that had recently been published and found many similarities, but also determined why our results differed when they did. It comes down to inherent problems associated with each genomic marker type. This project was also a long time coming, and it's great to see it out. Check it out early view right now at Genome Biology and Evolution. Over the last year we also adapted with our outreach and educational approaches. I lot of these included virtual talks with classrooms or clubs.I know zoom fatigue is a real thing now, but one of the more fun activities Ichthyology participated in was a collaboration between NHMLA and Nickelodeon. This ended up producing two series: the Science of Slime, and the Science of SpongeBob. Click on those links to check them out, as there are a lot of fun videos in both series. This last year also saw the return of in-person meetings. Last month I attended the Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (JMIH) in Phoenix, AZ. While attendance was low and the conference was shorter than usual, it reminded me of how much I missed seeing my colleagues in person and chatting about fishes. The smaller crowd made the talks a lot of fun as everyone could stay in one room the entire time and see all the wonderful fish talks together. While I look forward to next year's meeting in Tacoma, WA, this meeting will stick in my memory for some time. Last, but certainly not least, perhaps the most fascinating thing that occurred this last year was when a very special fish made it into our collection. Early on the morning of May 7th, 2021 a beach walker at Crystal Cove State Park in Orange County, CA noticed a strange fish that washed up onshore. What looked like a black ball of tar turned out to be a large female Pacific Footballfish (Himantolophus sagamius). This species is extraordinarily rare, especially of this size and in this excellent condition. After making quite a few calls, and with the help of CA Department of Fish and Wildlife, we were able to transfer this fish over the NHMLA. We are very fortunate to have this fish, and I'll post more about her in the future, but for now I'll leave you with this wonderful photo we took of her the day we thawed her out to preserve her: A beautifully intact adult female Pacific Footballfish that was found on the beach at Crystal Cove State Park in May of 2021.

The last thing I posted was a note that the museum was closing due to the coronavirus pandemic. That was back in March, and so much has changed in the interim that "the new normal" has become a popular phrase. So I figured I'd post about what this new normal means for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and for the Department of Ichthyology specifically. The NHMLA remains closed to the public and to researchers and visitors for the time being, and we are still under a loan moratorium for shipping or receiving loans under normal circumstances. This is simply because we cannot ensure that when we ship specimens that someone will always be there in a timely manner on the other side to receive them. However, Department of Ichthyology staff are now allowed back into the museum, so if you have an information request, or want us to look for a specimen for you, please send either Todd of myself an email and we will try to help you to the best of our abilities. Covid Cases continue to rise in Los Angeles County, so this is still a shifting situation and I will make another post as soon as visitors can come in again and once we can send loans again. The new normal for the Department of Ichthyology actually looks a lot like the old normal. While working from home we have still pursued research projects and continue to analyze data and digitize collections information. Since March we have had three papers published. The first was led by outstanding LSU graduate student Pamela Hart and focuses on the evolutionary history of blind cavefishes in North America. Pam did a ton of work on this publication and it details a great story about the loss of eyes in fishes. Go and check it out in Evolution. The second publication was led by NHMLA ornithology curator Allison Shultz, and includes several curators at the NHMLA. This perspective study looks at the use of museum specimens for studying urban evolution, and finds that museums are underutilized in this regard. As urban areas continue to grow in the 21st century, studies focusing on the impacts of urbanization on wildlife will certainly continue to increase. In this publication we make a variety of recommendations for different stakeholders on how to incorporate, add to, and support museums moving forward. Check it out in the special issue of Evolutionary Applications on Urban Evolution! The latest publication to come out details a large genetic barcoding effort in the United Arab Emirates that is linked to vouchered museum specimens in a reference collection started by the Environmental Agency – Abu Dhabi. This study is the largest bony fish barcoding study to date in the Arabian/Persian Gulf, and will add valuable information for a diversity of studies moving forward in the region. The value of the reference collection will only increase over time with researchers adding additional specimens, or re-examining specimens already housed in the collection. This study would not have been possible without the support of the Environmental Agency – Abu Dhabi, the hard work of all involved including LSU undergraduate students Layne Freeman and Genta Teruyama, and all of our UAE collaborators including Rima Jabado, Shamsa al Hameli, and Dr. Shaikha S. Al Dhaheri. You can read this study in the Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation. Finally, NHMLA ichthyology collections manager Todd Clardy presented work he has done on the ichthyoplankton of the Red Sea at the 44th Annual Larval Fish Conference, Virtual Larval Fish Town Hall at the end of June (video available on the linked website!) and will present more work that he's done on the zooplankton of the Arabian/Persian Gulf at the 6th International Marine Conservation Congress virtually next month, so be sure to check that out. Last, but absolutely not least, the past few months have really highlighted the racial inequalities faced by so many in our society. The names and the stories that we have all come to learn have really made us think deeply about how to be better and how to help those in need. Part of the NHMLA mission statement reads that we are a museum "of, for, and with LA", and we have had many intense and deep discussions over the past several months of how to improve as a museum, wether it's how we promote ourselves to our community, how we interact with guests at the museum, or how we approach science behind the scenes in our collections. There is a lot of work to be done moving forward, but I hope to be able to share some plans with you in the near future that we have been discussing. In the meantime I have added a new section on diversity and inclusion under the "Lab and Fish Collection" tab on this website to help make it clear that we welcome everyone from all walks to life to visit our collection, use our specimens, and discover fascinating facts about fishes and our planet. More to come on this soon.

Check back soon for more updates on what we're up to, the status of the museum and visiting our collections, and what we're doing to fight racism in science and in our community. Stay safe, everyone. I was originally hoping to write a post today detailing all of the creative outreach activities that the ichthyology collection has participated in the past several months, culminating in our Nature Fest that was scheduled for this last weekend. However, the rapid spread of the coronavirus, and the importance of a unified community response to slow this spread, means this post will not be about community outreach, but rather our commitment as a museum to joining the efforts of the community to minimize the spread of Covid-19. Nature Fest and all other events at the NHMLA have been postponed, and the museum is closed to the public until further notice. Likewise, our collections are closed to researchers during this time, and loans to other institutions may be delayed as well. If you are sending a loan back to us, please check with either Todd or myself prior to doing so to make sure we will be there to receive the loan. Please see the official announcement below, and check in with the NHMLA website for up-to-date information. We will get through this as a community, and once we do we will be back with more fun outreach events, new scientific discoveries, and fun fish facts. In the meantime, wash your hands, follow advice from the CDC, and stay safe.

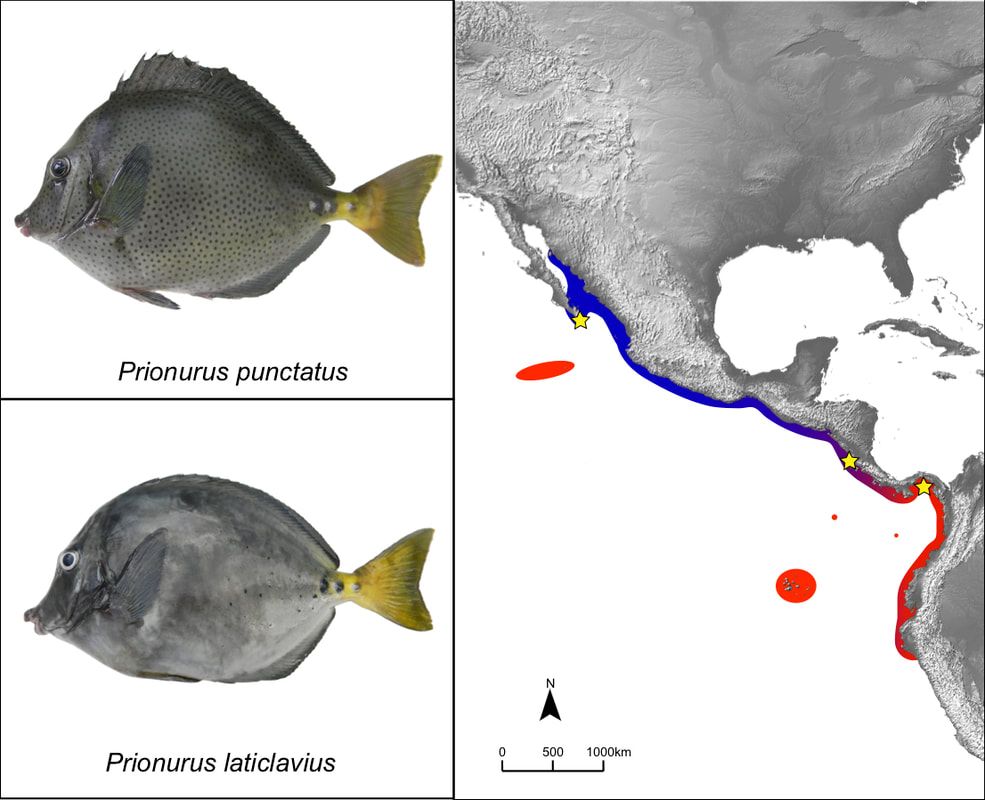

Just out this week, a new publication in collaboration with Luiz Rocha at the California Academy of Sciences and Prosanta Chakrabarty at the LSU Museum of Natural Science. Together we sequenced the mitochondrial genomes of two species of sawtail surgeonfishes. This genus of surgeonfishes isn't as common to come by as many of the others. Furthermore, it is the only genus of surgeonfishes that didn't have their mitochondrial genomes sequenced already. The addition of these two genomes allows us to examine the family as a whole, and can be used as a resource for future researchers. The publication is open access (freely available to download) and can be found in the journal Mitochondrial DNA Part B. Check it out and let me know what you think!

At the beginning of November I represented the NHMLA on a joint expedition to Costa Rica. This trip was led by Dr. Caleb McMahan at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and also included Dr. Arturo Angulo from the Zoology Museum at the University of Costa Rica. This expedition targeted freshwater drainages and brackish water habitats along the Atlantic slope of the country. We were generally collecting species we came across to observe variation and turnover in species assemblages as we sampled different river drainages along the coast, but we were also targeting several species that are the focus of ongoing research projects. As soon as we landed, however, the rain started pouring, and continued to do so for the first half of the trip. While we pressed on and sampled in the rain, the water levels of the streams and rivers we were sampling in were high, making it difficult to get certain species. Additionally, this created problems when we went to sample brackish waters, mainly in the sense that we couldn't find any brackish habitats... Even at the mouths of rivers, the outflows were so strong that all the water we tested with a salinity meter was completely fresh. This may sound like a horrible setup to a trip, but in reality everything turned out great in the end. The rains stopped, and we had clear skies for the second half of the trip. Additionally, we met up with a friend of Arturo's, Maribel Mafla Herrera, who works the non-profit association ANAI. Maribel was gracious enough to not only show us some of the fishes in southern Costa Rica, but as part of the ongoing biomonitoring that ANAI does she brought out her fish electroshocker, which helped us see a lot of species that we wouldn't have seen just using our seines and nets. At the end of the trip we spent a day in San Jose at the University of Costa Rica processing all of the fishes we collected and exploring their fantastic ichthyology collection. In the end, it was an extremely successful trip. We managed to find all of the target species we were interested in, collected a diversity of fishes, and got fantastic live-color photos of fishes that haven't been photographed live before. A huge thanks to all of those that helped this expedition, with special thanks to Caleb McMahan and the Field Museum, Arturo Angulo and the University of Costa Rica, Maribel Mafla Herrera, and ANAI.

After a busy last few weeks of summer that included the annual Joint Meet of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists and moving across the country, I have officially started as Assistant Curator of Ichthyology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County! I will be looking after the Robert J. Lavenberg fish collection, which houses specimens collected across the world. I am extremely excited to start this position, and can't wait to see what lies on those shelves. If you happen to be in the area, please stop on by!

Hot off the press: a new collaborative publication led by Chris Kenaley on remoras just became public this week! Remoras are a fascinating family of fishes, as they have a modified dorsal fin that acts as a suction disk, allowing them to attach to other fishes, turtles, or marine mammals. These hitchhiking fishes are also sometimes called suckerfishes due to this adaptation, and in this study we took a variety of approaches to understand the most that we could about how this behavior evolved. This included determining the relationships of the eight remora species, using microCT scans to get extremely detailed resolution of the suction disk, examining what animals all of the remora species were attaching to, and then finally figuring out how minute differences in the hosts effected how remoras could attach to them. Overall we recovered two main groups of remoras: a group of species commonly seen around reefs and those that are more pelagic. These groups of species differ in the number and type of host species that they hitchhike on, and finally these host differences seem to be associated with skin roughness and the hydrodynamic regime of the host, and the ability of the suction disk to adhere to that particular skin. If you'd like to read the specifics, the publication is out in Integrative Organismal Biology, an open source journal so anyone can read it for free!

The Indo-Pacific is the place to be if you're interested in coral reef critters. Sure, coral reefs exist all over the world within tropical latitudes, but the epicenter for biodiversity is the Coral Triangle, an area that spans roughly between the Philippines, Indonesia, and east towards Papua New Guinea. Understanding how the Coral Triangle formed, or why it is so diverse requires a broader approach that looks across both the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Quantifying evolutionary dynamics in the Indo-Pacific, however, is extremely challenging. This is foremost because the scale of the two ocean basins. Together, the portions of the Indian and Pacific Oceans that are considered to be part of the Indo-Pacific span roughly 180º longitudinally (aka half the planet)! To study the distribution, population dynamics, and history of species across this massive expanse takes time, dedication, and a big team of people.

Over the past two decades, independent labs have published a variety of population-level genetic studies across the Info-Pacific. These studies have focused on fishes, corals, or marine invertebrates, but were all largely independent of one another. In an effort to gain a more wholistic understanding of what's going on, several forward thinking scientists decided to pool all of their data and invite others to do so as well. Enter stage right: Diversity of the Indo-Pacific Network, or simply, DIPnet. While I could come up with my own way of describing it, the DIPnet mission statement puts it best: "DIPnet was created to advance genetic diversity research in the Indo-Pacific Oceans by aggregating (published) population genetic data into a searchable database so that original datasets can be utilized to address questions concerning conservation of marine biodiversity." This network and team of scientists finally allows us to look for more general patterns that are shared across life in the oceans. I am proud to be a part of this network, and extremely happy that the first publication from this massive effort has just been published in Global Ecology and Biogeography. Led by the talented Eric Crandall, this study aims to see if there is a correlation between processes acting within species, and between them throughout this region. To do this we looked for shared genetic breaks between regions, and then compared those to previous biogeographic schemes that have been hypothesized over the years. The previous hypotheses were based on species distributions, and therefore reflect processes acting on deeper evolutionary time scales, so by comparing population-level genetic data to these species-level biogeographic breaks we could see if there are ongoing processes that generate diversity over a variety of time scales. The short answer is that while some large-scale patterns hold true, there really isn't a strong connection between population and species-level processes in the 56 species included in this study. If you want to know why, please go check out the paper. It's open access, so anyone can read it! Huge thanks goes out to Eric, all of the co-authors, and all of the people who contributed their data to DIPnet, as this paper wouldn't have been possible without them. Hopefully this is the start of many publications and fruitful collaborations that together will help us understand the diversity of the Indo-Pacific, and coral reefs in general. I am happy to announce that my collaboration with Christopher Burridge at the University of Tasmania, and Prosanta Chakrabarty at Louisiana State University is finally published! This study uses a genomic approach to determine the evolutionary relationships among fishes in the suborder Cirrhitoidei, which contains hawkfishes (Cirrhitidae), marblefishes (Aplodactylidae), kelpfishes (Chironemidae), trumpeters (Latridae) and morwongs (Cheilodactylidae). This was my first foray into genomic methods and I started the lab work for this early on in my PhD. Slowly, the project grew until we had sampled almost every single species in this group, which has allowed us to confidently make taxonomic revisions. When I started this project it was known that Cheilodactylidae was not monophyletic, but no revisions had ever been made. Late last year the first major revision of this group was made by a Japanese team of researchers led by Katsuya Kimura using a morphological approach. Our study complements that study by adding in additional taxonomic sampling and genomic data. Hopefully the two of these papers together will settle any taxonomic confusion within this group of fishes.

New publication just out this week in Ecology and Evolution! Many species can easily be distinguished by outward appearances, either by differences in body shape, color, or other patterns. However, outward appearances can be deceiving, and sometimes the old adage "don't judge a book by it's cover" can apply to species as well. This is exactly what we found when we looked more closely at two surgeonfishes in the eastern Pacific. These two species are easily distinguished by the presence or absence of dark spots covering the body. Earlier work that I had published on this group hinted that there was something strange going on with these two species. So, I decided to go back and revisit the eastern Pacific. Working with a great group of collaborators (Moisés Bernal, Eva Salas, Erica Kenworthy, and Prosanta Chakrabarty), we were able to show through a variety of approaches that these two species are in fact, one. What causes some individuals to have dark spots and other to not have the? That's a great question, and one we still don't know the answer to. However, this research does highlight how speciation can (although clearly not always) happen along the coasts of the tropical eastern Pacific. It's an open access article, so go check it out if you're interested!

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |